-

Use Cases

Industrien

Getting started

-

Insights & Wissen

Für User

Support

This lesson assumes that you want to integrate a SICK sensor device via SOPAS protocol with the Cybus Connectware. To understand the basic concepts of the Connectware, please check out the Technical Overview lesson.

To follow along with the example, you will also need a running instance of the Connectware. If you don’t have that, learn How to install the Connectware.

Although we focus on SOPAS here, we will ultimately access all data via MQTT, so you should also be familiar with it. If in doubt, head over to our MQTT Basics lesson. When coming to the topic of the Rule Engine at the end it can be useful to have basic knowledge of JSON and JSONATA.

This article will teach you the integration of a SICK sensor device. In more detail, the following topics are covered:

The Commissioning Files used in this lesson are made available in the Example Files Repository on GitHub.

Our setup for this lesson consists of a SICK RFU620 RFID reading device. RFID stands for „Radio Frequency Identification“ and enables reading from (and writing to) small RFID tags using radio frequency. Our SICK RFU620 is connected to an Ethernet network on a static IP address in this lesson referred to as „myIPaddress“. We also have the Connectware running in the same network.

The protocol used to communicate with SICK sensors is the SOPAS command language which utilizes command strings (telegrams) and comes in two protocol formats: CoLa A (Command Language A) with ASCII telegram format, and CoLa B with binary telegram format, not covered here. Often, the terms SOPAS and CoLa are used interchangeably, although strictly speaking we will send the SOPAS commands over the CoLa A protocol format. In this lesson we use the CoLa A format only, as this is supported by our example sensor RFU620. (Some SICK sensors only support CoLa A, others only CoLa B, and yet others support both.)

The SICK configuration software SOPAS ET also utilizes the SOPAS protocol to change settings of a device and retrieve data. The telegrams used for the communication can be monitored with the SOPAS ET’s integrated terminal emulator. Additional documentation with telegram listing and description of your device can be obtained from SICK either on their website or on request.

For the integration we will need three pieces of information about the SOPAS commands we want to utilize:

1) Interface type: This part can be a bit tricky because the terminology used in device documentations may vary. The telegram listing of your device will probably group telegrams in events, methods and variables but sometimes you won’t find the term „variable“ but only the descriptions „Read“/“Write“.

2) Command name: Every event, method or variable is addressed using a unique string

3) Parameters: In case of variable writing or method calling some parameters may be required

The three interface types mainly have the following purposes:

The telegram listing from your device’s documentation is the most important source of this information. But for getting a hint of the structure of telegrams, we will take a short look at it.

For example, a command string for the RFU620 that we monitored with SOPAS ET’s integrated terminal emulator, could look like this:

sMN TAreadTagData +0 0 0 0 0 1

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)The first parameter in this string is the command type which in case of a request can be of the following for us relevant values:

| Value | command type | interface type |

|---|---|---|

| sRN | Read | variable |

| sWN | Write | variable |

| sMN | Method call | method |

| sEN | Event subscription | event |

The command type is sMN (where M stands for „method call“, and N for the naming scheme „by name“ as opposed to „by index“). This command name TAreadTagData enables us to read data from an RFID tag. Following the command name there are several space-separated parameters for the method call, for example the ID of the tag to read from. In this case we could extract the name TAreadTagData and the type method from the command string for our Commissioning File but yet don’t know the meaning of each parameter so we still have to consult the device’s telegram listing.

For this lesson we have identified the following commands of our RFID sensor:

| Name | Type | Parameters | Description |

|---------------|----------|-------------|-----------------------|

| QSinv | event | - | Inventory |

| MIStartIn | method | - | Start inventory |

| MIStopIn | method | - | Stop inventory |

| QSIsRn | variable | - | Inventory running |

| HMISetFbLight | method | color, mode | Switch feedback light |

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)The Commissioning File contains all connection and mapping details and is read by the Connectware. To understand the file’s anatomy in detail, please consult the Reference docs. To get started, open a text editor and create a new file, e.g. sopas-example-commissioning-file.yml. The Commissioning File is in the YAML format, perfectly readable for human and machine! We will now go through the process of defining the required sections for this example:

These sections contain more general information about the commissioning file. You can give a short description and add a stack of metadata. Regarding the metadata only the name is required while the rest is optional. We will just use the following set of information for this lesson:

description: >

SICK SOPAS Example Commissioning File for RFU620

Cybus Learn - How to connect and use a SICK RFID sensor via SOPAS

https://learn.cybus.io/lessons/how-to-connect-and-use-a-sick-rfid-sensor/

metadata:

name: SICK SOPAS Example

version: 1.0.0

icon: https://www.cybus.io/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Cybus-logo-Claim-lang.svg

provider: cybus

homepage: https://www.cybus.io

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)Parameters allow the user to customize Commissioning Files for multiple use cases by referring to them from within the Commissioning File. Each time a Commissioning File is applied or reconfigured in the Connectware, the user is asked to enter custom values for the parameters or to confirm the default values.

parameters:

IP_Address:

description: IP address of the SICK device

type: string

default: mySICKdevice

Port_Number:

description: Port on the SICK device. Usually 2111 or 2112.

type: number

default: 2112

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)We define the host address details of the SICK RFU620 device as parameters, so they are used as default, but can be customized in case we want to connect to a different device.

In the resources section we declare every resource that is needed for our application. The first resource we need is a connection to the SICK RFID sensor.

resources:

sopasConnection:

type: Cybus::Connection

properties:

protocol: Sopas

connection:

host: !ref IP_Address

port: !ref Port_Number

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)After giving our resource a name – for the connection it is sopasConnection – we define the type of the resource and its type-specific properties. In case of Cybus::Connection we declare which protocol and connection parameters we want to use. For details about the different resource types and available protocols, please consult the Reference docs. For the definition of our connection we refer to the earlier declared parameters IP_Address and Port_Number by using !ref.

The next resources needed are the endpoints which we supply data to or request from. Those are identified by the command names that we have selected earlier. Let’s add each SOPAS command by extending our list of resources with some endpoints.

inventory:

type: Cybus::Endpoint

properties:

protocol: Sopas

connection: !ref sopasConnection

subscribe:

name: QSinv

type: event

inventoryStart:

type: Cybus::Endpoint

properties:

protocol: Sopas

connection: !ref sopasConnection

write:

name: MIStartIn

type: method

inventoryStop:

type: Cybus::Endpoint

properties:

protocol: Sopas

connection: !ref sopasConnection

write:

name: MIStopIn

type: method

inventoryCheck:

type: Cybus::Endpoint

properties:

protocol: Sopas

connection: !ref sopasConnection

read:

name: QSIsRn

type: variable

inventoryRunning:

type: Cybus::Endpoint

properties:

protocol: Sopas

connection: !ref sopasConnection

subscribe:

name: QSIsRn

type: variable

feedbackLight:

type: Cybus::Endpoint

properties:

protocol: Sopas

connection: !ref sopasConnection

write:

name: HMISetFbLight

type: method

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)Each resource of the type Cybus::Endpoint needs a definition of the used protocol and on which connection it is rooted. Here you can easily refer to the previously declared connection by using !ref and its name. To define a SOPAS command we need to specify the desired operation as a property which can be read, write or subscribe and among this the command name and its interface type. The available operations are depending on the interface type:

| Type | Operation | Result |

|----------|-----------|--------------------------------------------|

| event | read | n/a |

| | write | n/a |

| | subscribe | Subscribes to asynchronous messages |

| method | read | n/a |

| | write | Calls a method |

| | subscribe | Subscribes to method's answers |

| variable | read | Requests the actual value of the variable |

| | write | Writes a value to the variable |

| | subscribe | Subscribes to the results of read-requests |

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)This means our endpoints are now defined as follows:

inventory subscribes to asynchronous messages of QSinvinventoryStart calls the method MIStartIninventoryStop calls the method MIStopIninventoryCheck triggers the request of the variable QSIsRninventoryRunning receives the data from QSIsRn requested by inventoryCheckfeedbackLight calls the method HMISetFbLightThe accessMode is not a required property for SOPAS endpoints and is by default set to 0. But if you want to access specific SOPAS variables for write access which require a higher accessMode than the default 0 (zero), look up the suitable accessMode and its password in the SICK device documentation. Regarding the accessMode the Connectware supports the following values:

| Value | Name |

|-------|-------------------|

| 0 | Always (Run) |

| 1 | Operator |

| 2 | Maintenance |

| 3 | Authorized Client |

| 4 | Service |

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)To this point we would already be able to read values from the SICK RFID sensor and monitor them in the Connectware Explorer or on the default MQTT topics related to our service. To achieve a data flow that would satisfy the requirements of our integration purpose, we may need to add a mapping resource to publish the data on topics corresponding to our MQTT topic structure.

mapping:

type: Cybus::Mapping

properties:

mappings:

- subscribe:

endpoint: !ref inventory

publish:

topic: 'sick/rfid/inventory'

- subscribe:

topic: 'sick/rfid/inventory/start'

publish:

endpoint: !ref inventoryStart

- subscribe:

topic: 'sick/rfid/inventory/stop'

publish:

endpoint: !ref inventoryStop

- subscribe:

topic: 'sick/rfid/inventory/check'

publish:

endpoint: !ref inventoryCheck

- subscribe:

endpoint: !ref inventoryRunning

publish:

topic: 'sick/rfid/inventory/running'

- subscribe:

topic: 'sick/rfid/light'

publish:

endpoint: !ref feedbackLight

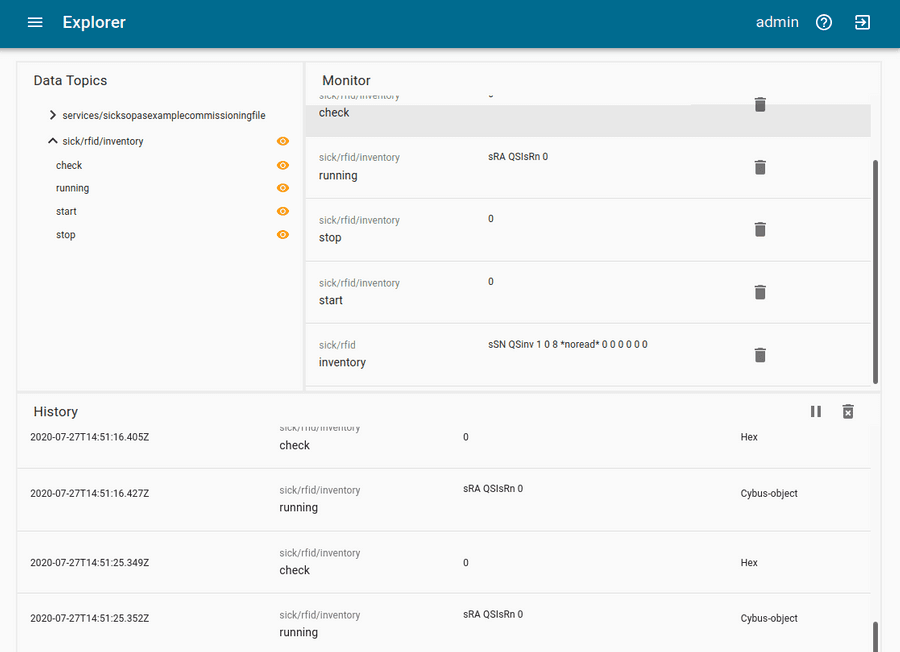

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)The mapping defines which endpoint’s value is published on which MQTT topic or the other way which MQTT topic will forward commands to which endpoint. In this example we could publish an empty message on topic sick/rfid/inventory/start to start RFID reading and publish an empty message on topic sick/rfid/inventory/stop to stop the reading process. While the reading (also referred to as inventory) is running, we continuously receive messages on topic sick/rfid/inventory containing the results of the inventory. Similarly when publishing an empty message on sick/rfid/inventory/check while having subscribed to sick/rfid/inventory/running, we will receive a message indicating if the inventory is running or not.

To provide parameters for variable writing or method calling you have to send them as a space-separated string. For instance, to invoke the method for controlling the integrated feedback light of the device just publish the following MQTT message containing a color and a mode parameter on topic sick/rfid/light: "1 2"

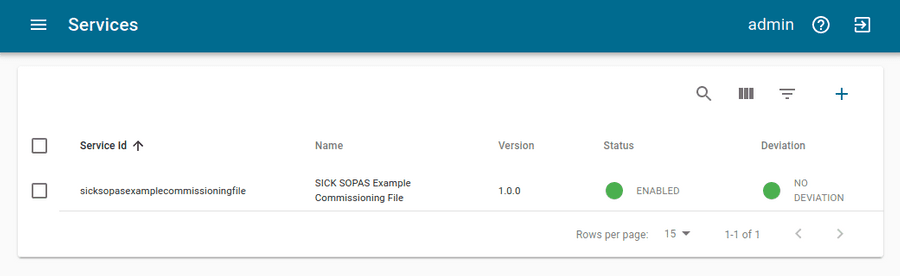

You now have the Commissioning File ready for installation. Head over to the Services tab in the Connectware Admin UI and hit the(+) button to select and upload the Commissioning File. You will be asked to set values for each member of the section parameters or confirm the default values. With a proper written Commissioning File, the confirmation of this dialog will result in the installation of a Service, which manages all the resources we just defined: The SOPAS connection, the endpoints collecting data from the device and the mapping controlling where we can access this data. After enabling this Service you are good to go on and see if everything works out!

The data is provided in JSON format and messages published on MQTT topics contain the keys "timestamp" and "value" like the following:

Although it is not represented by the Explorer view, on MQTT topics the data is provided in JSON format and applications consuming the data must take care of JSON parsing to pick the desired property. The messages published on MQTT topics contain the keys "timestamp" and "value" like the following:

{

"timestamp": 1581949802832,

"value": "sSN QSinv 1 0 8 *noread* 0 0 0 0 0 AC"

}

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)This particular example is an inventory message published on topic sick/rfid/inventory. You recognize its "value" is a string in the form of the SOPAS protocol containing some values and parameters. This is the original message received from the SICK device which means you still have to parse it according to SOPAS specifications. The Connectware offers a feature that can easily help you along with this task and we will take a look at it in the next step.

For this lesson we will demonstrate the concept of the Rule Engine with a simpler example than the above. We will look at the answer to a variable read request, which is more intuitively to read since those messages usually only contain the variable’s value. For instance, this is the answer to inventoryCheck on endpoint inventoryRunning:

{

"timestamp": 1581950874186,

"value": "sRA QSIsRn 1"

}

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)The SOPAS string contains just the command type (sRA = read answer), the variable name (QSIsRn) and the value 1 indicating that the inventory is running. But essentially we care about the value, because the command type is no further interesting for us and the information about the variable name/meaning is implied in the topic (sick/rfid/inventory/running). If this message is so easy to interpret for us, it can’t be too complicated for the Connectware – we just need the right tools! And that is where the Rule Engine comes into play.

A rule is used to perform powerful transformations of data messages right inside the Connectware data processing. It enables us to parse, transform or filter messages on the base of simple to define rules, which we can append to endpoint or mapping resource definitions. We will therefore extend the inventoryRunning resource in our Commissioning File as follows:

inventoryRunning:

type: Cybus::Endpoint

properties:

protocol: Sopas

connection: !ref sopasConnection

subscribe:

name: QSIsRn

type: variable

rules:

- transform:

expression: |

{

"timestamp": timestamp,

"value": $number($substringAfter(value, "sRA QSIsRn "))

}

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)We add the property rules and define a rule of the type transform by giving the expression which is a string in the form of JSONATA language. Rules of the type transform are direct transformations, generating for every input message, exactly one output message. The principle of the expression is, that you construct an output JSON object in which you can refer to keys of the input object (the JSON message of this endpoint) and apply a set of functions to modify the content. Please note that the pipe | is not part of the expression but a YAML specific indicator for multiline strings, denoting to keep newlines as newlines instead of replacing them with spaces.

We want to keep the form of the input JSON object, so we again define the key "timestamp" and reference its value to timestamp of the input object to maintain it. We also define the key "value" but this time we do some magic utilizing JSONATA functions:

$number(arg) casts the arg parameter to a number if possible$substringAfter(str, chars) returns the substring after the first occurrence of the character sequence chars in strThe second function will reduce the SOPAS string we refer to with value by returning just the characters after the string "sRA QSIsRn", in our case a single digit, which is then cast to a number by the first function. We can apply these functions in this way, because we know that the string before our value will always look the same. For more information about JSONATA and details about the functions see https://docs.jsonata.org/overview.html.

After installing the new Service with the modified Commissioning File, we do now receive the following answer to an inventoryCheck request (while inventory is running):

{

"timestamp": 1581956395025,

"value": "1"

}

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)This value is now ready-to-use and applications working with this data do not have to care about any SOPAS parsing!

The Connectware supports some more types of rules. To give you a hint, what might be possible, here is a quick overview:

parse – parse any non JSON data to JSONtransform – transform payloads into new structurefilter – break the message flow, if the expression evaluates to a false valuesetContextVars – modify context variablescov – Change-on-Value filter that only forwards data when it has changedburst – burst-mode that allows aggregation of many messagesstash – stash intermediate states of messages for later referenceFor more information about rules and the Rule Engine check out the Connectware Docs.

We started this lesson with a few SOPAS basics and learned which information about the SOPAS interface is required to define the Commissioning File for the integration of our SICK RFU620. Then we created the Commissioning File and specified the SOPAS connection, the endpoints and the MQTT mapping. Utilizing the Commissioning File we installed a Service managing those resources in the Connectware and monitored the data of our device in the Explorer of the Admin UI. And in the end we had a quick look at possibilities of preprocessing data using the Rule Engine to get ready-to-use values for our application.

The Connectware offers powerful features to build and deploy applications for gathering, filtering, forwarding, monitoring, displaying, buffering, and all kinds of processing data… you could also build a dashboard for instance? For guides checkout more of Cybus Learn.

This article covers Docker, including the following topics:

Maybe this sounds familiar. You have been assigned a task in which you had to deploy a complex software onto an existing infrastructure. As you know there are a lot of variables to this which might be out of your control; the operating system, pre-existing dependencies, probably even interfering software. Even if the environment is perfect at the moment of the deployment what happens after you are done? Living systems constantly change. New software is introduced while old and outdated software and libraries are getting removed. Parts of the system that you rely on today might be gone tomorrow.

This is where virtualization comes in. It used to be best practice to create isolated virtual computer systems, so called virtual machines (VMs), which simulate independent systems with their own operating systems and libraries. Using these VMs you can run any kind of software in a separated and clean environment without the fear of collisions with other parts of the system. You can emulate the exact hardware you need, install the OS you want and include all the software you are dependent on at just the right version. It offers great flexibility.

It also means that these VMs are very resource demanding on your host system. The hardware has to be powerful enough to create virtual hardware for your virtual systems. They also have to be created and installed for every virtual system that you are using. Even though they might run on the same host, sharing resources between them is just as inconvenient as with real machines.

Introducing the container approach and one of their main competitors, Docker. Simply put, Docker enables you to isolate your software into containers (Check the picture below). The only thing you need is a running instance of Docker on your host system. Even better: All the necessary resources like OS and libraries cannot only be deployed with your software, they can even be shared between individual instances of your containers running on the same system! This is a big improvement above regular VMs. Sounds too good to be true?

Well, even though Docker comes with everything you need, it is still up to you to assure consistency and reproducibility of your own containers. In the following article, I will slowly introduce you to Docker and give you the basic knowledge necessary to be part of the containerized world.

Before we can start creating containers we first have to get Docker running on our system. Docker is available for Linux, Mac and just recently for Windows 10. Just choose the version that is right for you and come back right here once you are done:

Please notice that the official documentation contains instructions for multiple Linux distributions, so just choose the one that fits your needs.

Even though the workflow is very similar for all platforms, the rest of the article will assume that you are running an Unix environment. Commands and scripts can vary when you are running on Windows 10.

Got Docker installed and ready to go? Great! Let’s get our hands on creating the first container. Most tutorials will start off by running the tried and true „Hello World“ example but chances are you already did it when you were installing Docker.

So let’s start something from scratch! Open your shell and type the following:

docker run -p 8080:80 httpd

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)If everything went well, you will get a response like this:

Unable to find image 'httpd:latest' locally

latest: Pulling from library/httpd

f17d81b4b692: Pull complete

06fe09255c64: Pull complete

0baf8127507d: Pull complete

07b9730387a3: Pull complete

6dbdee9d6fa5: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:90b34f4370518872de4ac1af696a90d982fe99b0f30c9be994964f49a6e2f421

Status: Downloaded newer image for httpd:latest

AH00558: httpd: Could not reliably determine the server's fully qualified domain name, using 172.17.0.2. Set the 'ServerName' directive globally to suppress this message

AH00558: httpd: Could not reliably determine the server's fully qualified domain name, using 172.17.0.2. Set the 'ServerName' directive globally to suppress this message

[Mon Nov 12 09:15:49.813100 2018] [mpm_event:notice] [pid 1:tid 140244084212928] AH00489: Apache/2.4.37 (Unix) configured -- resuming normal operations

[Mon Nov 12 09:15:49.813536 2018] [core:notice] [pid 1:tid 140244084212928] AH00094: Command line: 'httpd -D FOREGROUND'

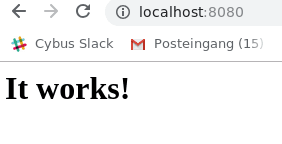

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)Now there is a lot to go through but first open a browser and head over to: localhost:8080

What we just achieved is, we set up and started a simple http server locally on port 8080 within less than 25 typed characters. But what did we write exactly? Let’s analyze the command a bit closer:

docker – This states that we want to use the Docker command line interface (CLI).run – The first actual command. It states that we want to run a command in a new container.-p 8080:80 – The publish flag. Here we declare what Docker internal port (our container) we want to publish to the host (the pc you are sitting at). the first number declares the port on the host (8080) and the second the port on the Docker container (80).httpd – The image we want to use. This contains the actual server logic and all dependencies.IMAGES

Okay, so what is an image and where does it come from? Quick answer: An image is a template that contains instructions for creating a container. Images can be hosted locally or online. Our httpd image was hosted on the Docker Hub. We will talk more about the official docker registry in the Exploring the Docker Hub part of this lesson.

HELP

The Docker CLI contains a thorough manual. So whenever you want more details about a certain command just add --help behind the command and you will get the man page regarding the command.

Now that we understand what we did we can take a look at the output.

Unable to find image 'httpd:latest' locally

latest: Pulling from library/httpd

f17d81b4b692: Pull complete

06fe09255c64: Pull complete

0baf8127507d: Pull complete

07b9730387a3: Pull complete

6dbdee9d6fa5: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:90b34f4370518872de4ac1af696a90d982fe99b0f30c9be994964f49a6e2f421

Status: Downloaded newer image for httpd:latest

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)The httpd image we used was not found locally so Docker automatically downloaded the image and all dependencies for us. It also provides us with a digest for our just created container. This string starting with sha256 can be very useful for us! Imagine that you create software that is based upon a certain image. By binding the image to this digest you make sure that you are always pulling and using the same version of the container and thus ensuring reproducibility and improving stability of your software.

While the rest of the output is internal output from our small webserver, you might have noticed that the command prompt did not return to input once the container started. This is because we are currently running the container in the forefront. All output that our container generates will be visible in our shell window while we are running it. You can try this by reloading the webpage of our web server. Once the connection is reestablished, the container should log something similar to this:

172.17.0.1 - - [12/Apr/2023:12:25:08 +0000] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 45

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)You might have also noticed that the ip address is not the one from your local machine. This is because Docker creates containers in their own Docker network. Explaining Docker networks is out of scope for this tutorial so I will just redirect you to the official documentation about Docker networks for the time being.

For now, stop the container and return to the command prompt by pressing ctrl+c while the shell window is in focus.

Now that we know how to run a container it is clear that having them run in an active window isn’t always practical. Let’s start the container again but this time we will add a few things to the command:

docker run --name serverInBackground -d -p 8080:80 httpd

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)When you run the command you will notice two things: First the command will execute way faster then the first time. This is because the image that we are using was already downloaded the last time and is currently hosted locally on our machine. Second, there is no output anymore besides a strange string of characters. This string is the ID of our container. It can be used to refer to its running instance.

So what are those two new flags?

--name – This is a simple one. It attaches a human readable name to our container instance. While the container ID is nice to work with on a deeper level, attaching an actual name to it makes it easier to distinguish between running containers for us as human beings. Just keep in mind that IDs are unique and your attached name might not!-d – This stands for detach and makes our container run in the background. It also provides us with the container ID.Sharing resources: If you want to you can execute the above command with different names and ports as many times as you wish. While you can have multiple containers running httpd they will all be sharing the same image. No need to download or copy what you already have on your host.

So now that we started our container, make sure that it is actually running. Last time we opened our browser and accessed the webpage hosted on the server. This time let’s take another approach. Type the following in the command prompt:

docker ps

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)The output should look something like this:

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

018acb9dbbbd httpd "httpd-foreground" 11 minutes ago Up 11 minutes 0.0.0.0:8080->80/tcp serverInBackground

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)ps – The ps command prints all running container instances including information about ID, image, ports and even name. The output can be filtered by adding flags to the command. To learn more just type docker ps --help.Another important ability is to get low level information about the configuration of a certain container. You can get these information by typing:

docker inspect serverInBackground

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)Notice that it does not matter if you use the attached name or the container ID. Both will give you the same result.

The output of this command is huge and includes everything from information about the image itself to network configuration.

Note: You can execute the same command using an image ID to inspect the template configuration of the image.

To learn more about inspecting docker containers please refer to the official documentation.

We can even go in deeper and interact with the internals of the container. Say we want to try changes to our running container without having to shut it down and restart it every time. So how do we approach this?

Like a lot of Docker images, httpd is based upon a Linux image itself. In this case httpd is running a slim version of Debian in the background. So being a Linux system, we can access a shell inside the container. This gives us a working environment that we are already familiar with. Let’s jump in and try it:

docker exec -it -u 0 serverInBackground bash

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)There are a few new things to talk about:

exec – This allows us to execute a command inside a running container.-it – These are actually two flags. -i -t would have the same result. While i stands for interactive (we need it to be interactive if we want to use the shell) t stands for TTY and creates a pseudo version of the Teletype Terminal. A simple text based terminal.-u 0 – This flag specifies the UID of the user we want to log in as. 0 opens the connection as root user.serverInBackground – The container name (or ID) that we want the command to run in.bash – At the end we define what we actually want to run in the container. In our case this is the bash environment. Notice that bash is installed in this image. This might not always be the case! To be safe you can add sh instead of bash. This will default back to a very stripped down shell environment by default.When you execute the command you will see a new shell inside the container. Try moving around in the container and use commands you are familiar with. You will notice that you are missing a lot of capabilities. This has to be expected on a distribution that is supposed to be as small as possible. Thankfully httpd includes the apt packaging manager so you can expand the capabilities. When you are done, You can exit the shell again by typing exit.

Sometimes something inside your containers just won’t work and you can’t find out why by blindly stepping through your configuration. This is where the Docker logs come in.

To see logs from a running container just type this:

docker logs serverInBackground -f --tail 10

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)Once again there are is a new command and a few new flags for us:

logs – This command fetches the logs printed by a specific container.-f – Follow the log output. This is very handy for debugging. With this flag you get a real time update of the container logs while they happen.--tail – Chances are your container is running for days if not months. Printing all the logs is rarely necessary if not even bad practice. By using thetail flag you can specify the amount of lines to be printed from the bottom of the file.You can quit the log session by pressing ctrl+c while the shell is in focus.

If you have to shut down a running container the most graceful way is to stop it. The command is pretty straight forward:

docker stop serverInBackground

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)This will try to shutdown the container and kill it, if it is not responding. Keep in mind that the stopped container is not gone! You can restart the container by simply writing:

docker start serverInBackground

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)Sometimes if something went really wrong, your only choice is to take down a container as quickly as possible.

docker kill serverInBackground

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)Note: Even though this will get the job done, killing a container might lead to unwanted side effects due to not shutting it down correctly.

As we already mentioned, stopping a container does not remove it. To show that a stopped container is still managed in the background just type the following:

docker container ls -a

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)container – This accesses the container interaction.ls – Outputs a list of containers according to the filters supplied.-a – Outputs all containers, even those not running.CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

ee437314785f httpd "httpd-foreground" About a minute ago Exited (0) 8 seconds ago serverInBackground

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)As you can see even though we stopped the container it is still there. To get rid of it we have to remove it.

Just run this command:

docker rm serverInBackground

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)When you now run docker container ls -a again you will notice that the container tagged serverInBackground is gone. Keep in mind that this only removes the stopped container! The image you used to create the container will still be there.

The time might come when you do not need a certain image anymore. You can remove an image the same way you remove a container. To get the ID of the image you want to remove you can run the docker image ls command from earlier. Once you know what you want to remove type the following command:

docker rmi <IMAGE-ID>

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)This will remove the image if it is not needed anymore by running docker instances.

You might have asked yourself where this mysterious httpd image comes from or how I know which Linux distro it is based on. Every image you use has to be hosted somewhere. This can either be done locally on your machine or a dedicated repository in your company or even online through a hosting service. The official Docker Hub is one of those repositories. Head over to the Docker Hub and take a moment to browse the site. When creating your own containers it is always a good idea not to reinvent the wheel. There are thousands of images out there spreading from small web servers (like our httpd image) to full fledged operating systems ready at your disposal. Just type a keyword in the search field at the top of the page (web server for example) and take a stroll through the offers available or just check out the httpd repo. Most of these images hosted here offer help regarding dependencies or installation. Some of them even include information about something called a Dockerfile..

While creating containers from the command line is pretty straight forward, there are certain situations in which you do not want to configure these containers by hand. Luckily enough we have another option, the Dockerfile. If you have already taken a look at the example files provided for httpd you might have an idea about what you can expect.

So go ahead and create a new file called ‚Dockerfile‘ (mind the capitalization). We will add some content to this file:

FROM httpd:2.4

COPY ./html/ /usr/local/apache2/htdocs/

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)This is a very barebone Dockerfile. It basically just says two things:

FROM– Use the provided image with the specified version for this container.COPY– Copy the content from the first path on the host machine to the second path in the container.So what the Dockerfile currently says is: Use the image known as httpd in version 2.4, copy all the files from the sub folder ‚./html‘ to ‚/usr/local/apache2/htdocs/‘ and create a new image containing all my changes.

For extra credit: Remember the digest from before? You can use the digest to pin our new image to the httpd image version we used in the beginning. The syntax for this is:

FROM <IMAGENAME>@<DIGEST-STRING>

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)Now, it would be nice to have something that can actually be copied over. Create a folder called html and create a small index.html file in there. If you don’t feel like writing one on your own just use mine:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<h1>That's one small step for the web,</h1>

<p>one giant leap for containerization.</p>

</body>

</html>

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)Open a shell window in the exact location where you placed your Dockerfile and html folder and type the following command:

docker build . -t my-new-server-image

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)build– The command for building images from Dockerfiles. – The build command expects a path as second parameter. The dot refers to the current location of the shell prompt.-t – The tag flag sets a name for the image that it can be referred by.The shell output should look like this:

Sending build context to Docker daemon 3.584kB

Step 1/2 : FROM httpd:2.4

---> 55a118e2a010

Step 2/2 : COPY ./html/ /usr/local/apache2/htdocs/

---> Using cache

---> 867a4993670a

Successfully built 867a4993670a

Successfully tagged my-new-server-image:latest

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)You can make sure that your newly created image is hosted on your local machine by running

docker image ls

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)This will show you all images hosted on your machine.

We can finally run our modified httpd image by simply typing:

docker run --name myModifiedServer -d -p 8080:80 my-new-server-image

Code-Sprache: YAML (yaml)This command should look familiar by now. The only thing we changed is that we are not using the httpd image anymore. Instead we are referring to our newly created ‚my-new-server-image‘.

Let’s see if everything is working by opening the Server in a browser.

By the time you reach these lines you should be able to create, monitor and remove containers from pre-existing images as well as create new ones using Dockerfiles. You should also have a basic understanding of how to inspect and debug running containers.

As was to be expected from a basic lesson there is still a lot to cover. A good place to start is the Docker documentation itself. Another topic we didn’t even touch is Docker Compose, which provides an elegant way to orchestrate groups of containers.

Sie müssen den Inhalt von reCAPTCHA laden, um das Formular abzuschicken. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten mit Drittanbietern ausgetauscht werden.

Mehr InformationenSie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von Facebook. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Mehr InformationenSie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von Instagram. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Mehr InformationenSie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von X. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Mehr Informationen